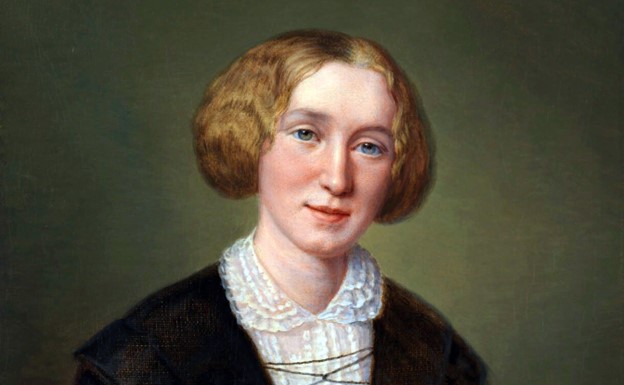

In these ethics she was both timeless and distinctly Victorian. Adam Bede, her first novel, was published in 1859 – the same year as Charles Darwin’s On the Origin Of Species, which stripped nature of the need for a divine creator, and John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, which for many people finally stripped ethics of the need for divine commandments.

George Eliot shared the view that both these men expressed: that human goodness springs from human nature alone and needs no religious or divine underpinning and she thought, as they did, that the discoveries of both science and history were making this fact plain.

But hers is a humanism often left out of her biographies, which frequently acknowledge her loss of faith, but not the positive affirmation of life and its meaning which animated her life, and underpins her novels. Like free thinkers before and since, she rejected the confines of supposed respectability where they conflicted with her own conscience, blazing a trail for those others whose moral convictions led them to rebel and reform. She lived her values. The romantic warmth George Eliot added to the humanist intellectual tradition of the nineteenth century is not the only influence that moulded this change, but I believe it is a significant one.

In fact I believe George Eliot had no equal in the nineteenth century for her commitment to human solidarity, sympathy. We see it in her novels – her deep understanding of the inner life of others. We see it in her essays – powerful critiques and expositions of radical ethical ideas. And we see it in the example of her life itself – a life worth celebrating. A great writer, a great Midlander, and a very great humanist.